Click on the images to get

a better picture.

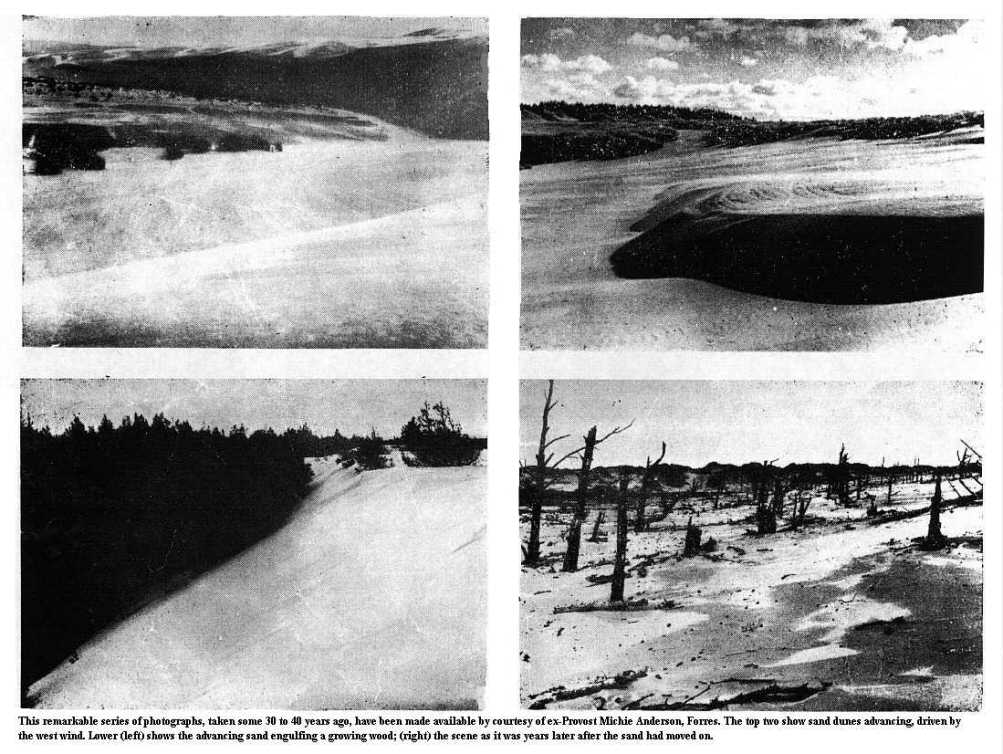

Click on the images to get

a better picture.Memories of Scotland's One-Time Desert

THE KINNAIRDS AND CULBINBy D. KEITH MacEWEN

Few people can have had a more intimate association with the famous Culbins than the writer of this article.

Mr. MacEwen, who is now retired from the postal service at Dyke, has known the region since earliest boyhood, and it has never failed to exert its fascination for him.

In the following article he recounts something of the strange history of the one-time desert - now largely forested - and describes incidents of his many expeditions in search of archaeological remains and other relics of by-gone times.

ALEXANDER KINNAIRD was the last laird of Culbin to bear a name associated with the estate in question since 1440. Born in April, 1655, he was the son of Thomas Kinnaird and Anna, sister of Lord Elphinston, and was duly baptized in "the lang Kirk o' Dyke."

His father, unfortunately, was frequently at variance with the laird of Brodie, and his own peat moss having already disappeared beneath the ever-encroaching sand, Kinnaird senior had resorted to "pirating" supplies from that of his neighbour. There were march disputes, too, and it must have been a great relief to the embarrassed laird of Brodie that the Bishop of Moray was "ever willing to decerne betwixt them."

"Young Coubin" (Alexander) was destined in turn to become a thorn-though of a more insidious sort-in the laird of Brodie's flesh, for there is a revealing entry in the Brodie diaries lamenting the unfortunate outcome of a chance meeting in Forres: "Oh, so easy a prey as I am to temptation, the Lord knows." Young Kinnaird was a fairly frequent visitor to Brodie Castle, and reading between the lines of the delightfully Pepysian entries, one can readily appreciate that, had not the obligations of hospitality, plus a fine sense of what was due to a neighbouring proprietor, been such paramount considerations, Alexander's room would have been far more preferable than his company.

For, Jamshyd-like, he "gloried and drank deep" and his reckless mode of life earned him a reputation far from savory. Inevitably, too, it assured him a place in the legendary lore of an estate slowly being invested by an invader as inexorable as Time itself-the ever-advancing sand.

In my boyhood a legend, analogous to that of the "Flying Dutchman," was still current. Kinnaird, it averred, had been entombed for his sins in the Mansion House by the October sandstorm of 1694, which closed forever the strangely tangled saga of the Barony of Culbin.

It was during a Saturday night's card game at the Mansion House that one of the party, observing it was close on midnight, threw down his hand. an example which his fellow Covenanters were not slow to follow. Exasperated at being denied his revenge, for the cards had run badly for him, Culbin, an avowed Royalist, swore a reckless oath to the effect that he would play into the Sabbath "Gin the Deil suld come tae gie him a gemme!" And Satan, opportunistic as always, did. with fatal consequences to the Laird.

On the death of his father in 1691, Alexander Kinnaird succeeded to the estate, but despite the income from the enforced sale of what was left, was compelled to petition Parliament for protection from his creditors. This granted, for his insolvency was attributed to an "act of God," he emigrated to Darien where he died, supposedly in 1700. though the manner of his death is unknown.

His second wife, Mary. daughter of Alexander, 11th Lord Forbes, and widow of Hugh Rose of Kilravock, outlived him by many years. If, as was said, she was gey ill tae live wi'," the unfortunate man may well have deemed exile the lesser of two evils.

Early Visits To Culbin

Though there were other ways of entering Culbin, I preferred to follow a track a few hundred yards west of the farm of Wellhill. Familiar to salmon-fishing crews from coastal fishing stations, and used occasionally by picnic parties and others as a short cut to the sea, it was clearly defined and preferable to the more arduous approach through a strip of hummocky, rankly-growing heather which separated the arable farmland from the outer dunes of Culbin.

Between the latter and the Sands was a very attractive belt of scattered Scots fir interspersed with thickets of sapling birches. The comparatively level ground was carpeted with a cotoneaster-like dwarf growth and the resultant coolness and shade were to be recalled nostalgically at times when Culbin's temperatures soared in the heat of high summer.

In the lesser dunes nearby there was a corner which invariably yielded up bronze bosses, roughly half an inch in diameter and perforated. These had probably been used in the ornamentation of saddlery or upholstery, but I have never found them elsewhere in all the length and breadth of Culbin.

It was here one day that I plucked a seed stem and was surprised to discover that what I had assumed to be a rather odd-looking head was in reality a coin! It had been crudely pierced, as Culbin coinage often was, and the stem had grown through the hole and borne it aloft. The coincidence loses nothing in its strangeness when I add it was the only coin I ever found on the spot in question.

Choice of route, as indicated in my opening paragraph, was influenced by various factors, but it was only on entering the Sands that the direction of the wind became important. indeed significant. Viewing the widespread panorama of Culbin Sands from the west, one observed that the dune level tended to attain its culminating point near their eastern boundary, the Bay of Findhorn. Indeed a particularly prominent dune in this area, "Lady Culbin," was reputedly the tomb of the Manor House, which revealed its chimneys about a century and a half ago and has never been located since. Though experiments to expose the site with explosives proved abortive, Major Chadwick, R.E., late proprietor of Binsness Rouse, was more successful in his efforts to control the sand-drift by afforestation and the planting of protective belts of strategically placed clumps of rhododendrons. Naturally, traces of his pioneering, absorbed by the intensive and sustained reclamation of the Forestry Commission, are not easily identifiable nowadays, but they still exist nevertheless.

As forestry workers fight woodland fires from behind, so did the seeker of relics go with the drift of the sand when approaching his objective. In default of a calm day, preferably the aftermath of a wet night, to make for an area, even against the lightest of summer breezes, was hopelessly frustrating. I can remember an artist, contemplating a study of the Sutors across the Moray Firth, lament the difficulty of transferring the oil to his canvas because of the grittiness it acquired under such conditions.

If I were temporarily interested in Stone Age relics, then I gravitated, naturally to the rocklike, red-brown pre-historic strata, locally known as pan." As a boy, however, I generally chose to go for the chocolate-brown belts that lay at the foot of the dunes, the still-furrowed arable land which in a day long past earned the Barony of Culbin the title of 'the Granary of Moray."

Morasses Between The Dunes

Miniature glens between the dunes appeared to offer an easy, if winding. approach, but their presence was often illusory.

The sand was generally loose and yielding and there was always the possibility of blundering into gluey morasses, accumulations of winter rainfall camouflaged by summer's sand-drift. Though disconcerting, these were innocuous enough: for very rarely did I sink beyond knee-depth. Even so, it was possible to "plowter" through for a long way before emerging thankfully onto firmer ground.

The weather slopes of the dunes, on the other hand. afforded good going and more direct approach, and what a thrill it was to top the rise and be avalanched, willy-nilly, to the relic bed below If I may be forgiven a digression, one of my most engaging memories of Culbin visits is that of a visit from Findhorn, when the going was in reverse as it were. Two young ladies of the party, espying a typical search area, immediately kilted their ankle-length skirts, and with a gay challenge, sped down the long slope with the swift grace of young Atalanta. There were no golden apples to be retrieved, but everybody was pleased when one of them picked up a perfect specimen of a yellow-striped, blue-glass Venetian bead. This was a much-prized find and in sixty years of Culbin I have never experienced the joy of finding such another, though I have retrieved fragments of the bead in question often enough.

I carried a stick, which trailed behind whilst 1 concentrated on the ground before me. When the "beat" ended, a pace to the right or left, as the case might be, before setting off again insured a reasonably searching scrutiny.

A curious feature of the arable land, where the furrows were still plainly discernible, was the absence of end-rigs, but I leave it to others with more knowledge of agricultural techniques to explain the why and wherefore of this peculiarity.

Finds were numerous and varied, ranging from domestic articles like pins, needles and thimbles, to coins, rings, beads, brooches, buckles, etc. There was an abundance of glazed mediaeval pottery, too, and I knew of a shoreward site where pottery of crude and obviously ancient manufacture could be picked up from time to time.

Wind vagaries might expose hitherto unseen areas at any time and it was on one of such areas I came by a Roman brooch, now in the British Museum.

Considering the multiplicity and nature of the finds there is, I think, every reason for believing that, in its final stages at least, the evacuation of Culbin must have been so hasty, confused, and panic-stricken that much was left behind that would otherwise have been salvaged.